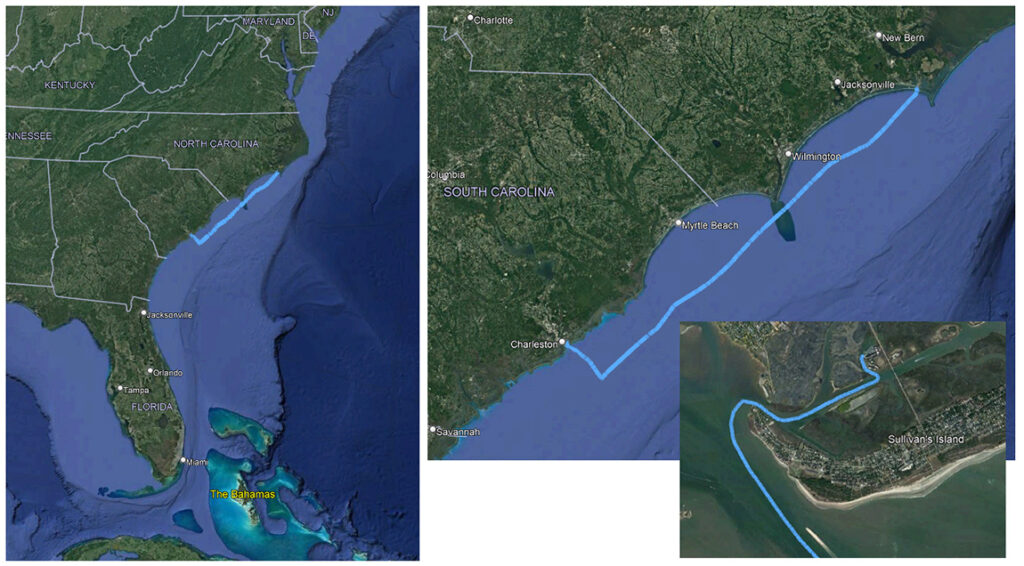

What a ride! Sonora had a headsail out on a pole and the main set on the opposite side. Both boom and the pole were made fast with their respective downhauls, pulling her sails out for the strong winds to fill. She looked incredible, with her canvas out on both sides, running rigging creating shapes of a triangle on all of her spars. Looking like this, waves ranging from six to eight feet would catch up to her, and her stern would rise a bit as she surfed down the face of the wave. Gusty winds pushed her forward and her bow would cut deeply into the ocean, creating spray and foam as she charged forward. Wing on wing baby! Go Sonora! It was mostly like this for two days, as we sailed thirty nautical miles off shore off the coasts of the Carolinas.

We saw some amazing sights and put up with some challenging circumstances. I felt very good about myself, my crew, and the boat. Packed full of spirited sailing, the last few days had been a blur, requiring some thoughts to be gathered to bundle all of the pieces of events. It was a lively time — and I mean that in the literal sense. Every moment I felt more alive than I do most other times of my life. Focused, performing, but also managing fatigue. Dallace was put through the same test on his very first offshore sail.

Sunday morning was still very gusty at the Beaufort anchorage. We could hear the waves crashing into the beach on the other side of the barrier island, and the wind ripped through the tops of the trees. The most recent forecast had said that the winds would die down and that we had twenty three knot gusts offshore. It sure sounded more than that. It was supposed to die down as the day went by. At around one in the afternoon the wind was showing to have nineteen knot gusts. It still sounded like it was much more, and it probably was, but started weighing anchor then. By three, we were leaving the protected waters, winding around the barrier islands. We were excited about what lay ahead. Gradually, as we left the protection of land, the wind and sea states increased.

Eventually we were in fifteen knots of steady wind with gusts of twenty knots about half of the time. The waves a bit more stacked than we’d like. It wasn’t until further into the trip where I’d become a seaman experienced enough to know this, but these were some residual waves from the stronger winds of the prior days. Autopilot was able to keep up, and the wind was blowing right in the direction we wanted to go. So as soon as we left the channel, we got the pole out and deployed both sails.

It was to stay that way for the next forty-eight hours! At some point, a slight wind shift caused us to tack over the pole and boom. But that was about it. Then the sun set. This whole trip, thanks to the shorter days of the season, felt like a giant night sail with a little bit of daylight as respite.

This is how the first two days went. We were always reefing or shaking out a reef, maintaining a steady four to five and a half knots, keeping up with the wind conditions. The constant element was the waves. It was very rarely under four feet, with a substantial portion of it being five feet with some bigger waves thrown in the mix. This made the boat extremely rolly. No matter what we were doing, we had to deal with the rolls. Oh, the ever present rolls.

The boat would try to steady itself for about three wave cycles. On either the fourth of the fifth one, she’d feel like she was about to broach, and start itself on an incredible roll cycle of twenty to thirty degrees on each side. Whether you were on deck standing watch, or below trying to sleep, you had to deal with this roll. The sound of halyards and antenna cables smacking the mast, the sails losing and filling with wind, and at times, the loud bang of the rigging and genoa protesting these forces. My new headsail is made of an incredibly tenacious material that doesn’t really stretch, and at times the headsail would suddenly fill with air on the up-roll. It made a loud bang every time. I knew the rigging could handle this easily, but it was still a bit nerve wrecking. Especially when I was steadying myself on my bunk, trying to sleep. This went on for all three days of the trip. Alas, that is what dead downwind sailing is. We were making great speed. With our weather window, it wasn’t worth it to sail further upwind and add a ton of distance. So I just put up with the fact that I’d fall out of my bunk every once in a while, and wondered why I hadn’t made lee-cloths for this trip.

Dallace at went below and heated us cans of soup. As the skipper of this boat, it was worrisome watching Dallace go below on our rolly boat and steady a pot of hot liquid as he brought the contents to a boil. But I am really bad about self-care during passages, so it was good that someone was stepping up to get us some real food. I normally don’t like canned soup, but it tasted so good.

We were constantly fighting the cold. Whether it is thirty five degrees or fifty degrees, it always felt cold. This was because we’d wear the least we can get away with. Harsh weather gear like this is very cumbersome. We each had our own huddle spot on the cockpit where we could be more shielded from the wind. We’d strategically keep one or both hands in the pocket, and when necessary, put on gloves. I’d constantly shift my fleece neck gaitor up and down to balance warmth and comfort. But hot canned soup was the best weapon in the fight against cold.

We had plenty of distractions. This leg has been in incredibly clear conditions, and at night, the star field was always there for us to see. Everything would be lit up by the eerie moonlight in the first half of the night. The peaks of the waves, the spray coming off of Sonora, and the deck would have a highlight from this glow. The next half, the moon would bid us adieu and the shy group of star would make themselves seen. Dallace heard some animals taking a breath at the surface, undoubtedly some cetaceans. Though it was at night, he finally got to see the offshore dolphins he wanted to see. We sailed through some meteor showers too. You could fix your eyes at a certain quadrant of the sky, and within minutes, you’d see four or five meteors.

I didn’t see any starlink satellite trains this time, nor flashes from military gunnery exercises. But I did see a few low flying fighter aircraft doing night combat maneuvers. Two of them seemed to chase each other across the sky. Your eyes and brain are trying to make sense of the rapidly moving lights. Then your ears hear the loud military jet engines. Only then are they revealed as what they are in the spotlight of your mind. Every once in a while, they’d drop decoy flares. The first time I saw flares, it was very confusing. A bright light would appear as a dot, then after three seconds, another one would appear, while a small sparkly object kept moving along. Another seemed to dump over ten flares at once. It left a spectacular cluster of light in the night sky. But these were decoy flares and not illumination flares. An illumination flare would make this patch of the sea as bright as day. Instead, they looked like small, tiny, fireworks made just for us.

So much of short handed passages are about fatigue management. Mind you, Dallace is very fit. He does these long runs every day. I’m not as fit, but I still try to keep myself in shape. Still, we move slow, deliberate movements whenever we can. Even if we have to maneuver the sailboat, we do it step by step – there is almost always more time than you think. Out of concern for the other, we wait until we are sure we can fall asleep before going below, but we also try to stay ahead of the fatigue curve and start out sleep cycles early. Even on watch, out in low traffic areas, I catch very short cat-naps with a timer. It’d almost be self-sufficient — but these rolly waves nickel-and-dimed our bodies and we got more tired by the hour. There is no ego here, just us and our natural, physical limitations. The sea humbles you.

The morning of the last day, today, the winds really picked up. I woke up to take over watch and stuck my head out the hatch board — the waves behind the boat are incredible. My face is blasted by a gust of wind. We immediately reef in everything, which makes everything a bit less intimidating. Some of these gusts were past thirty knots.

Could we manage another two to three days of this? I guess we could. With two sets of hands, we could always hand-steer. But in cruising, there is no point in beating up yourself if you don’t have to. We were only twenty five nautical miles from Charleston. This would eat up another precious day for Dallace, who had a hard limit on how long he could be away from home. But Dallace is smart; he listens to me when I tell him its not worth it. He hasn’t truly gotten his butt kicked at sea yet. I have.

To make it to Charleston, we had to turn north. This required a trip to the bow to take down the pole, a gybe to get on the correct tack, and then an upwind sail in the wrong direction, then a tack over to get sailing in the correct direction. Its hard work but we take it in stride. We think of the sequence of actions several times over. Then we talk it over with your mate. Do it slow, take your time, and do everything deliberately. In sailing, you almost never have to rush anything if you do it in the right sequence. There is always time, so we use it! Our safety depends on it.

The boat is moving up and down quite a bit. But all of Sonora’s movements are a bit damped, and all the corners are rounded off. Great boat. We get the boat moving upwind and this is where she really shines. Dallace had the same impression as I did when I first did my heavy upwind sailing offshore. Just as it was for me, this type of sailing was the first time he was really impressed with the boat. “The boat is really doing what its designed to do.” He’d say. We had the sails balanced where a gust would push the bow into irons a tiny bit, lessen the heel and the boat to regain her composure, before the autopilot would correct the course back. It worked really well, close to what a good human helmsman would do.

There aren’t that many boat designers out there, compared to how many people design products in other industries. But the size of the niche is made up by several millennia of experience. Each boat out there is a result of accumulation of a very deep, vibrant and an immense pool of knowledge. Sometimes fought over wars, with an expensive price paid in blood. Sonora may sometimes glide along a quiet sea on a light breeze. But today she was almost gracefully climbing and slicing through big blue water waves.

We’d climb up a big hill of water, banked to the leeward side, looking down at a valley of sea. Me and Dallace are sitting right next to each other, leaned against the windward combing, with our feet braced on the other set of seats. We looked down to the leeward side. It was like looking down a cliff, staring at a churning floor made of sea water. But that moment is fleeting. Soon we are back down, the bow of the boat cutting through the next wave with the gracefulness that lies in between a fencer’s cut and a lumberjack’s axe stroke. As she goes up the next hill, the crest of the wave blasts out the leeward side of the hull as spray. All the while the wind is howling. Its absolutely incredible. Exhilarating, and somewhat terrifying.

We decided to practice a heave-to. Conditions were challenging, but just enough where we still felt safe doing so. What a rare opportunity! These heavy weather heave-tos are never as graceful as I hope. But there is no doubting that it works. Once we were hove-to, instead of rocking in pitch and yaw, the boat simply moves up and down. Its scary seeing your genoa sheet pressed against your shrouds that hard, but the rigging will take it as long as you watch for chafe. With the same elderly speed we used in every other maneuver, we tack the boat over and start sailing upwind on the other tack – for about four hours.

The drive box for the auto pilot is mounted on Sonora’s pedestal tube via two hose clamps. The small pulley on the drive box is connected to the steering wheel via a belt. That is how it is configured from the factory. Over time, this setup slowly gets loose, and it gets loose enough for the belt to start skipping the teeth of the drive gear. When this happens, the AP gets very confused and you have to hand steer the boat back to heading and re-engage. I’ve never really adjusted it since I installed the unit. We keep a careful eye on it, sometimes keeping the belt engaged by my foot pressing lightly on the drive box. This is something I should address soon.

As we approach Charleston, we watched for ship traffic as Charleston is a busy port. Since this is an unscheduled stop, we also had to call the marinas in the area. The popular ‘mega-dock’ marinas are full. The other one next to USS Yorktown museum is expensive. We pick this marina just off the Intracoastal Waterway east of the city and reserve a slip there. We got a really cool view of a container ship coming out of the harbor. We see a mysterious, water-world looking contraption sitting to the west of the channel jetty. We think its a target of some sort for the Navy to shoot at, as there are unexploded ordnance warnings in those waters. Anchor there at your own risk! Enjoying the suddenly calm waters, we make the eastern turn into the Intracoastal. We dock uneventfully and get the boat fueled up. We both got a bit upset when we discovered that the marina shower is out of hot water. How ridiculous! There are only two reasons to pick up a slip instead of anchoring, and one of them was a hot shower! Also ridiculous is how we put up with never-ending harsh conditions just to complain about hot showers.

We also spent about thirty minutes hard-mounting the autopilot to the pedestal. I’m glad I carry all these spare fasteners! I simply drilled and tapped two holes into the soft aluminum and fixed the drive box bracket with two bolts and anti-seize. I’m so tired and my mind is still out in those heavy seas, that I barely notice how beautiful South Carolina is, especially the area surrounding this marina.

A part of me is really bummed out to cut this trip in half with only hundred eighty nautical miles left to St. Augustine. But we made the right call. We would still be getting pounded out there, and continue getting pounded after it got dark. So why suffer? This should be the sailing cruiser’s mantra. Why suffer? But I can’t help second guessing myself. I am happy, but I also feel like we gave up on something.

It is supposed to be fifty degrees tonight, which is the warmest we’d ever been. I am probably never using the heater again as I head into warmer climate, so we fired up the heater. I was barefoot in the toasty cabin! Warm feet – a guilty pleasure on this cruise. We still had plenty of arduous sailing left, so we shamelessly enjoyed this luxury while we basked in this feeling of accomplishment; we had done over two hundred nautical miles in two days, and finished the single biggest US leg of the trip south.

Glossary:

pole (whisker pole) – A spar (fancy boat word for tubes or rods) that is mounted on the mast to pull a headsail out to the side, usually to increase the frontal area to increase the surface area for the wind to push on a deep downwind run.

downhaul – Any line that pulls something down on a sailboat. In this case, the pole has a downhaul. A boom downhaul is typically at the front to pull it down at the gooseneck. However, the boom also has a downhaul in the form of a preventer at the other end of the boom. Actually, on Sonora, there is no distinction, except in the manner it is used, between a preventer and a pole downhaul. I use the same two lines interchangeably.

preventer – A line that prevents the boom from gybing around. On Sonora, it is simple: a line is attached to the boom end, then led up to a turning block at the bow, then led back to the stern and fastened to a stern cleat. This is the strongest way to rig a preventer.

genoa – A headsail that has a substantial overlap with the mainsail when it is pulled towards the stern. The overlap is measured as a percentage. For example, Sonora’s 130% genoa overlaps the mainsail by 30% of its sail area.

lee-cloth – A piece of cloth to prevent a person from falling out of their bunk when the boat is heeled over. Unfortunately, for most of us, our monkey reflexes aren’t as good as we hope them to be.

leeward – Opposite of windward. Windward is the direction the wind is coming from, and leeward is the direction the wind is going to.

heave-to – A maneuver that stops the boat dead in its tracks. It is also an excellent storm management tactic. You back-wind the headsail and trim the main to produce almost neutral forward thrust. Magic happens, and the boat sails backwards very slowly into its own wake, calming its motions.

genoa sheet – A sheet is any line (not rope!) used to trim and control a sail. So the main sheet controls the mainsail, jib sheet controls a jib, and a genoa sheet controls the sheet.

shroud – A mast on a modern cruising boat is typically held up in tension by a steel cable at the bow, stern, and the beam (sides). The side cables are called shrouds.

drill and tap – The act of drilling a hole, and cutting threads into it with a tool called a tap.

3 thoughts on “Brawn and Brains Under a Meteor Shower (Offshore to Charleston 12/14/21)”

I want to add a comment here: I do not recommend sailing through the Frying Pan shoals like I did. We did it in broad daylight under favorable conditions at high tide. And we only draw 4.5 feet. Any on-shore conditions can create inescapable surf that can pound you into the leeward shore.

Really enjoy your writing style. Your words carry the emotional punch of the moment. Probably the best sailing writing I have read in five years. Please hurry for the next! I’m interested in the rest!

Thanks Jeff! Have you subscribed to the blog? Its separate from my business mailing list — you’ll only get the blog updates whenever a new post is made!