“I know you hate motoring, but you should just motor. Its just something you do when you are cruising.” My friend Anna’s face popped up next to my head like a spirit bubble, not unlike Mr. T’s spirit bubble in the dumb high school movie spoof that is Not Another Teen Movie. It happened a few times on this leg.

Today, my total distance traveled is approximately 740 nautical miles. This is longer than the longest sailing cruise I’d done previously on Sonora, which was the 600 nautical miles that I traveled during my solo DelMarVa cruise. I did a bulk of this leg – about 440 nautical miles, with Dallace.

Even though the cold showers at the marina we stopped in Charleston really pissed us off, it was extremely nice sleeping in a still vessel, instead of a rocking one. Although inadequate, I could not over emphasize to anyone how nice this felt. Unfortunately, this stop probably meant that Dallace couldn’t join me for the Bahamas passage as he had to go home back to his family and back to his work.

We still haven’t had our youtube-picturesque complete passage yet. Every single leg had been challenging. The intracoastal should have been easy, but it wasn’t. And a forty knot storm on the Chesapeake bay. The cold was relentless, with icy winds penetrating every seam of my foul weather gear. Rolling, pitching, jerking motions on repeat. Gusty winds and sea state that required constant attention to the sails. And there was the rain that just made everything colder and a bit slipperier. All of this somewhat changed this leg, but we had some new challenges. And along with improved conditions, came interesting events.

We left the Charleston jetty just after noon. Spirits were high, and sea state was mild near the coast. Wind was blowing in a way where if we headed directly south, then gybed over west, then did another gybe south-southwest, we can make a direct run to St. Augustine. So two maneuvers to cover about two hundred miles and arrive at the destination. No big deal, right?

As the afternoon rolled by and we headed further offshore, seas picked up to similar conditions we were experiencing prior to this leg. At least we were moving quickly. Our speed made good was five and a half knots, on a point of sail that was deep downwind. But noticeably less downwind than when we were wing-on-wing on our previous leg. So even though we had conditions similar to yesterday, it was noticeably more comfortable. However, by now, we had gotten ‘seasoned’ to the rolly motions and we’d have gladly traded comfort for a faster course. We had also fixed the autopilot mounting, so with the sails balanced, the autopilot handled the seas with ease.

Five o’clock post meridiemrolled by lazily and it was time to do a gybe. We do the maneuver a bit faster than what we were doing yesterday, but it goes just as smooth. We’re starting to become a well oiled machine. It feels great. And whenever we are doing what I call ‘sailor shi*,’ it is a respite to the ever-present difficult conditions of the blue-water seas. It gives us something to do and makes me feel like I have a purpose, instead of merely being a primate hanging on for the ride.

A sailing vessel relies on sails and keels producing lift for stability, though some part of that comes from what is called form stability. Especially when running downwind, you want the boat to out-run the waves as much as possible. That’ll minimize wave action affecting your boat’s movement. Later that night, conditions subsided a bit. Unfortunately, like most of the time, wind subsides more than the waves. It often takes much longer for waves to subside as they retain some energy even after the winds ceases to drive them. So we are back to getting our butts kicked. It is the same sea, and the same endless rolling of the boat we had before Charleston. We painfully watched the boat creep through the remaining miles. We resigned to our fate and we just made do with it. Both me and Dallace tried hard not to complain, lest we bring each other’s spirits down. Our off-watches only get us about an hour or two of light sleep, each of our nights full of crazy dreams that we talked about whenever we had a changing of the watch.

One thing about Dallace — in addition the fact that he is an eager crewmember who already knows how to sail, he has these incredible sea-eyes. He’d consistently spot other ships and lights at least ten seconds before I did. On one of the more boring watch sessions with both of us on the deck Dallace spoted sails on the horizon. Few moments later, I see it too.

With nothing else to distract us, we watch the sailboat, named Interlagos get closer and closer. We noted the distance, speed and aspect information displayed on the Automatic Identification System and compared it with with what our eyes could see. She gets pretty close, and then executes a gybe, but she looks dead in the water. We continue observing her to make sure she’s okay, and only take our attention away when she’s making way again.

It was kind of a ‘pirate ship’ moment. Sailboat spotting is just like how it is in those age-of-sail movies! It all makes sense — the excited shouts of ‘sail!’ that you hear from a character aloft, peeping through their spyglass. You see the white sails of the vessels before you see anything else. It wasn’t easy to visually figure out another boat’s heading, so comparing it with the AIS information was good practice. I was also a bit proud that our skills as a sailor since we are able to execute these maneuvers smoothly. That being said, Interlagos cruised almost twice as fast as we did with only her mainsail up.

Later in the night, when it was my watch and Dallace was sleeping, I spotted a light over the horizon. Since I wasn’t transmitting my position on AIS, I radioed Bear Away to let them know where I was. We exchanged some information. The skipper of Bear Away had a French accent. You meet so many French sailors in the cruising world. He let me know that my radar return was very low, and that he only saw me on radar when I was a couple of miles away from him. Apparently I have a stealth sailboat. He did tell me that my stern light was very bright and that he saw me long before he got a radar contact. This is going to be something I have to think about, as flying my cumbersome radar reflector while I’m trying to sail didn’t seem like a good. Maybe I’ll bolt on a reflective rod or something. We chatted a bit. He was heading to Fernandina Beach and also hoped to make it to the Bahamas. It was a nice respite. Solo night watches can get pretty lonely, and its nice to see someone else up and awake in this little patch of the sea. Safe journeys, Bear Away.

Between my yawns and strained scans of the horizons, all sorts of thoughts rushed into my head. Having so much time to introspect and recall is a wonderful part of sailing. While I looked for strange objects and lights in the sea and the sky, I let myself remember a moment from the passage to Charleston. It was another one of those strange lights stories. I’d been below sleeping in my bunk when Dallace woke me up. There was an element of franticness in his voice, so I immediately got up and poked my head above the hatch. He pointed at a blinking amber light, which by now, was being passed on the starboard side less than thirty meters from Sonora. We sat there trying to figure out what it was. I text messaged my friend Bill, who told me that flashing yellow lights in the middle of the ocean are typically weather buoys. What didn’t make any sense to all three of us was that this light was on the surface of the water. The lights from the buoys are typically high up in the air. We had written it off as a mystery and focused on our passage.

It wasn’t until much later that I realized that this was probably a submarine’s periscope. Either a periscope itself, an antenna, or some sort of sensor. Peacetime submarines can sometimes display an amber flashing light on these devices. This may have been, in hindsight, the scariest moment of the Atlantic ocean passages. Depending on the orientation and actions of the submarine, we could have had an incident. Submarines have a very large propellers to reduce their revolutions and minimize noises coming from a quickly turning screw. A submarine turning her large screws disturb incredible volumes of water, which can sink smaller surface vessels. Still, I didn’t feel any visceral feelings of terror thinking about this, but I did wonder if our sailboat, as silent as a boat can be, was ever seen by this submarine.

We did our final gybe and turned south. As I went down for my off-watch, we noticed a lot of commercial traffic anchored offshore, towards the east coast. Its always kind of trippy to see all those lights on the horizon towards the the coast of Savannah, Georgia.

The next day was mainly us trying to avoid using our engine as much as possible. Wind was steadily decreasing. We started shaking out reefs and fiddling with other sail controls. Eventually, we gave up and started motor-sailing. This is when I noticed that my engine was running on two cylinders until it was warmed up. Easy fix – this usually happens when the dinosaur ignition system on the old engine gets dirty. At my next stop, I have to remember to clean the points and rotor.

Many hours later, I was getting frustrated. Boat was still rolling, and my cold-rash flared up and started itching again. The other thing that was really frustrating us was the condensation. After many days of offshore sailing, salt covered virtually all of the deck. Salt absorbs moisture. Now that we were at lower latitudes, the air was really humid. At night time, this humidity would eventually get soaked up on the salt present on the ship’s surfaces. Inside the cabin, on the deck, on our bibs and jacket, and even our hands. Then the water would mix with the salt and make everything feel sticky. Furthermore, our salty hands seemed to be sponges, adding more pain to our already calloused hands. My spirits sunk a little bit. It took some effort to hold it together – when you are with crew, frustration really affects other people. At least the sun would rise soon.

Sun was peeping over the horizon. Just as I was feeling down, I saw some grey figures appear just under the surface next to our boat. Torpedo-like figures swimming along all sides of Sonora, just under the surface. They were dolphins! A bit smaller than the bottlenose dolphins I’d see in my local waters, but just as playful. It really made me forget all of the misery. I went up to the bow and watched them play around the boat. They looked like they were timing Sonora’s bow rising and falling, and making a game out of swimming right under the boat just as the bow came down. It was a small pod of spotted Atlantic dolphins. As Dallace says: it doesn’t matter if you’re the saltiest crusty sailor ever. Everyone flips out in joy when dolphins come visit.

I don’t know what it is that draws them to small boats. Maybe its the shared intelligence, knowing you aren’t the only smart, sentient thing around here. Knowing that that you aren’t the only creature on earth that love showing off and being playful. Whatever the reason, the humans and dolphins both found joy together, with only the water’s surface and a few feet of distance separating them. The appearance of dolphins marked the first time on this cruise that actually felt warm. We got down to our shorts quickly. I sat at the bow for a long time giggling and staring, letting myself be a bit uninhibited.

Day two of this leg would have a lot of steaming. We still tried to sail as much as we can, hoisting everything back up and turning then engine off. But the speed just wasn’t there. And the wind wasn’t going to pick up for another day. Anna was right. Sometimes you just have to fire up the engine and get to next safe harbor. No use being stuck out in the abyss, crawling along on at some unbearably slow speed. Eventually, our cycle of turning the engine on and off stopped, and the continuous hum of the engine took over, even as the stars came out. More dolphins came to visit my steadily humming boat. Seeing their vague, grey shapes underneath the water was really cool, though they don’t seem to hang around a steaming sailboat as long they do with a boat that is under sail.

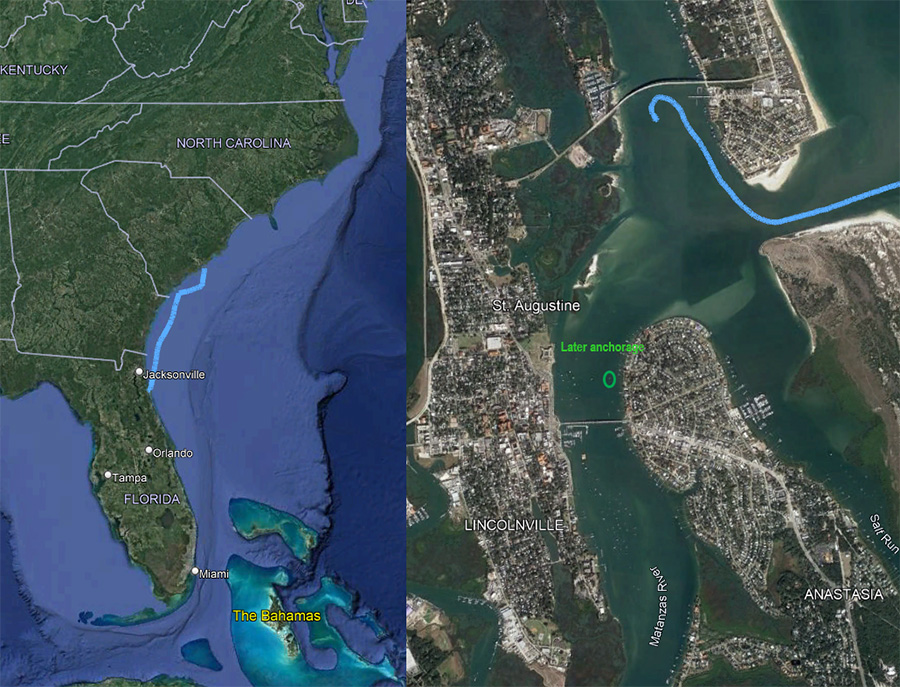

St. Augustine inlet isn’t particularly challenging, but the shoals shift often enough that the channel isn’t shown on the charts. Instead, the local authorities move the channel markers to mark the location of the deeper water. These markers are also not on the charts. They have to be visually spotted.

Although we had tried to slow down the boat and get into St. Augustine during sunrise, it was still dark when we got there. Dallace was a real help in negotiating this inlet at night. My dodger windshield was encrusted with salt and condensation. It made it hard to see out of. Dallace, with his excellent night vision, would sit on the port side and I’d sit on the starboard side to get an unobstructed view. We’d compare what we saw and check it against the charts, and bounce off ideas to each other and come to a consensus on where to steer the boat. Under calm, but dark seas, we made it into St. Augustine.

We turned north and anchored just south of the Vilano bridge, west of the Vilano beach. This place is beautiful. I don’t know why I have decade old memories of St. Augustine being ugly. Its the oldest city in our country and there was plenty to see and do. The twenty five minute dinghy ride to the city marina was very scenic, except for a sailboat boat hard aground, leaning against the downtown sea wall from a wicked nor’easter over a month ago. Although I was unaware at the time, this was a foreshadow of the events to come.

Despite having arrived, we both had a lot of things that needed doing. Once ashore, I went to grab a shower under some blissful hot water to make up for the hot shower that was robbed from us in Charleston. Dallace went to ship off excess luggage back home and to got breakfast. Doing things alone was just fine after all that time spent together.

My friend Sebastian gave me tips on where to anchor further South so that I’d be closer to the marina. This long dinghy ride would be impractical, so I went back to Sonora to move her to the southern anchorage. In my head, it was going to be easy and I’d be back before my dryer was finished. I was a fool. I was tired and not thinking straight. It takes half an hour just to get back to the boat! What was I thinking. I’d be fumbling around on the boat for hours while my laundry occupied a dryer in a busy laundry room.

After doing some scouting runs, it took us three tries to properly position Sonora at the new anchorage. I really wanted to just ‘call it a day,’ but anchorages weren’t going to get any easier as I headed further South. So I welcomed the practice and took as many tries as I needed to get it just right. Dallace didn’t welcome it as much, but he was the guy at the bow hauling up the heavy ground tackle while all I had to do was manipulate my engine controls and turn the wheel. I wanted to get used to never allowing myself to be lazy with my anchor. Pick it up and move when I need to. Move only a few meters in a direction or another if I have to. One should never feel lazy about re-anchoring, because its such a crucial thing for your sailboat. Fortunately, when I was done and made it back to shore, I discovered no one had stolen my clothes.

I was going to miss Dallace. This was his first offshore cruise. Over four hundred miles done in a span of six days. And we had truly done it together! Dallace was a real crewmember and first mate. He was such good help on the boat. He was patient, communicated clearly and had a good attitude that never lowered your spirits. His already existing sailing knowledge and ability to independently make a decision was just icing on the cake.

Dallace had a morning flight back to Beaufort, and then he would have to drive eleven hours to make it back to his home in Cincinnati. I knew he wasn’t my responsibility anymore, but I caught myself worrying about his trip back.

And just like that, I was alone again. But with a few days to rest and explore St. Augustine, I welcomed this time I had to myself.

DelMarVa – A portmanteau of Delaware, Maryland and Virginia, this is the name of the peninsula that makes up the eastern shore of the Chesapeake Bay. You can circumnavigate this peninsula by going through the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal (as well as the Bay itself and parts of the Atlantic ocean). This trip is frequently called “The DelMarVa” by cruisers.

Gybe – A downwind maneuver that involves turning the boat so that the wind comes from one side off the tail of the boat, to another.

Form stability – The form of a boat’s stability that comes from the boat’s lateral bouyancy. Essentially, the floatation (pockets of air in Sonora‘s example) on the sides of the boat gives her this form of stability. In another example, a deep, skinny hull would give a boat less form stability, but a flat, wide hull would give a boat more form stability.

Post meridiem – Believe it or not, this isn’t a fancy-boat-word. P.M. is an acronym for Post Meridiem, as is Ante Meridiem is for A.M.

Automatic Identification System – This is a system carried on boats that transmits crucial information necessary to avoid a collision. Sonora only carries a receiver, so she does not broadcast her position on this network.

Shaking out a reef – Reefing is the act of reducing sail area to manage heavier winds. Shaking out of reef is the act of un-doing the reefing.

Steaming – As opposed to sailing. The correct term to describe a vessel underway using engine power and not her sails.

2 thoughts on “How To Be a Salty Sailor: Sail South, Avoid Submarines (12/15/21 Offshore to St. Augustine)”

Really enjoy reading your posts. When I retire I’d love to sail with you

Thanks Maggie!